As a historian specializing in the 18th century, I often find myself drawn to the everyday challenges people faced and the ingenious solutions they devised. While we might associate the Enlightenment with grand philosophical debates and scientific discoveries, it was also a period of significant, often unheralded, technological advancement in areas that directly impacted daily life. Today, I want to explore one such area: ventilation.

We often think of ventilation as a modern concern, tied to air conditioning and complex HVAC systems. However, the need for fresh air and the understanding of how to manage it dates back much further. In the 18th century, particularly in urban centers and in specific environments like hospitals, mines, and public buildings, poor air quality was a serious problem. The consequences ranged from discomfort and the spread of disease to potentially fatal conditions in industrial settings.

My research has led me to discover the growing awareness of ‘bad air,’ or miasma, believed to cause illness. While the germ theory of disease was still a distant concept, the empirical observation that stagnant, foul air was unhealthy spurred innovation. This wasn’t just about opening windows; it was about creating systems.

Consider the challenges faced in places like hospitals. The crowded conditions and the nature of illness meant that air could quickly become stagnant and dangerous. Physicians and engineers began experimenting with ways to actively move air. This often involved mechanical devices, such as large fans or bellows, sometimes powered by hand, water, or even early steam engines. The goal was to create a continuous flow of fresh air, expelling the ‘noxious vapors.’

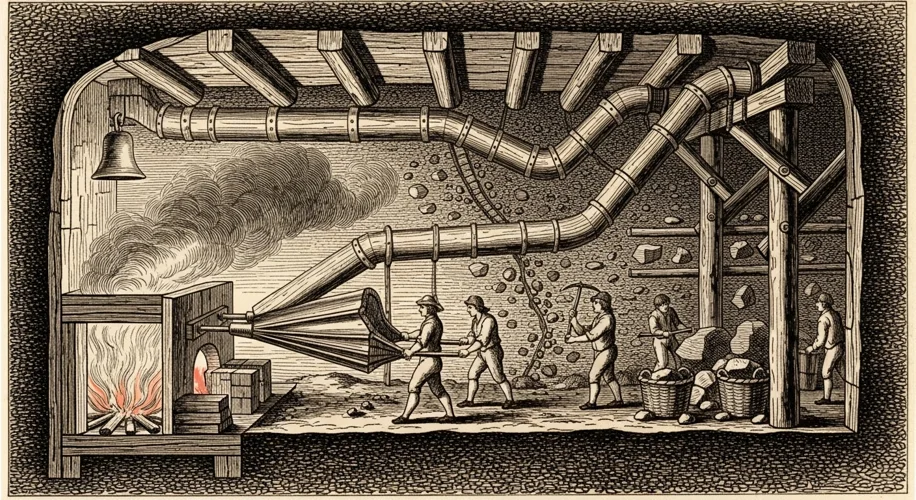

In mines, ventilation was a matter of life and death. Dangerous gases like methane (firedamp) could accumulate, leading to explosions. Early ventilating systems in mines often involved huge furnaces at the bottom of shafts, which heated the air, making it rise and creating a draft that pulled fresh air down other shafts. It was a rudimentary but effective application of basic physics.

We can also see this drive for better air circulation in the design of homes and public spaces. Architects and builders started to consider airflow more deliberately, incorporating features like chimneys designed not just for heating but also for drawing air out. The development of scientific instruments also played a role, allowing for more precise measurements of air quality and movement.

It’s fascinating to consider how these efforts, though perhaps primitive by today’s standards, laid the groundwork for our modern understanding of air quality and environmental control. They reflect the era’s spirit of empirical observation and practical problem-solving. The engineers and thinkers of the 18th century, armed with limited tools but driven by necessity and a burgeoning scientific curiosity, were already working towards creating healthier, more comfortable living and working environments. It’s a testament to the human drive to innovate, even in the most fundamental aspects of life, like the very air we breathe.