It’s fascinating, isn’t it? We talk about evolution as if it’s this obvious, fundamental truth about life. But when you step back, you realize it wasn’t always this clear. For centuries, people observed the world, saw variations in plants and animals, and noticed fossils of creatures unlike any alive today. Yet, the formal theory of evolution, as we know it, took a surprisingly long time to be formally proposed.

So, why the delay? Was it just a lack of fancy instruments like electron microscopes or DNA sequencers? While modern tools certainly help us understand the mechanisms of evolution with incredible detail, the core idea itself didn’t necessarily require them.

The World Before Darwin

For most of human history, the prevailing view was that life was created in its current form. This idea, often called creationism or fixity of species, was deeply woven into cultures and religions. Challenging this wasn’t just a scientific disagreement; it was often a societal one.

Before the 18th and 19th centuries, the scientific method was still developing. While observations were made, systematic data collection and controlled experimentation weren’t as widespread. Think about it: naturalists like Buffon and Erasmus Darwin (yes, Charles Darwin’s grandfather!) observed variations in species and suggested that life might change over time. However, their ideas were often speculative and didn’t form a cohesive, testable theory.

The Intellectual Hurdles

One of the biggest hurdles was simply the concept of deep time. Our understanding of how old the Earth is, and by extension, how long life has had to change, was very limited. Early estimates of Earth’s age were thousands of years, not the billions we now know. If the Earth is young, there isn’t enough time for significant evolutionary changes to occur.

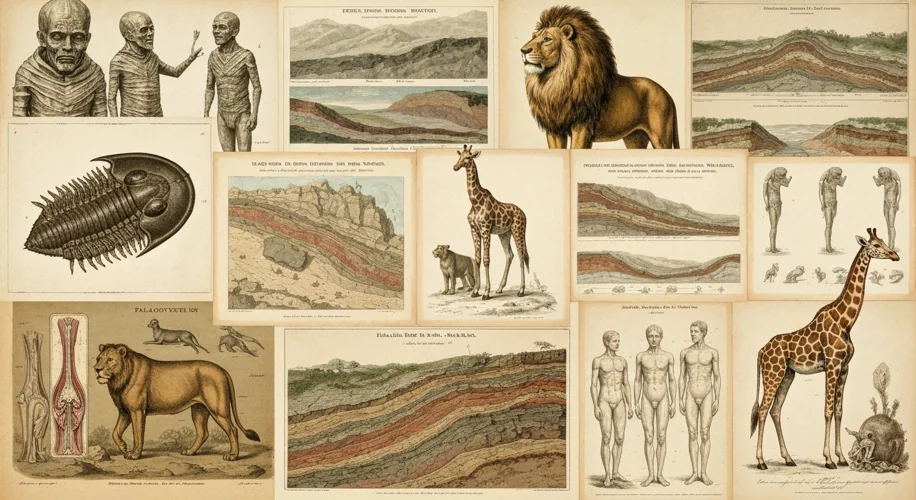

Geologists, however, began to reveal a different story. Through studying rock layers (stratigraphy) and fossils, they started to piece together a history of Earth that stretched back far beyond biblical timelines. Figures like James Hutton and Charles Lyell provided crucial evidence for an ancient, dynamic planet, paving the way for evolutionary thinking.

The Power of Observation and Ideas

Even without advanced tech, keen observation was key. Naturalists meticulously cataloged species, noting their similarities and differences. They saw how animals in different environments had distinct traits that seemed well-suited to their surroundings.

It was this careful accumulation of observations, combined with a growing understanding of geology and a willingness to question established ideas, that laid the groundwork. Charles Darwin and Alfred Russel Wallace, working independently, synthesized these threads. They looked at things like:

- Fossil Records: Evidence of past life that differed from present life.

- Geographic Distribution: Why similar species lived in different places, and why some islands had unique species.

- Anatomical Similarities: Why different animals shared fundamental body plans.

- Artificial Selection: How humans could breed plants and animals for specific traits by selecting desirable individuals.

This last point, artificial selection, was particularly powerful. Darwin essentially asked: If humans can change species over generations by selective breeding, could nature do something similar, but over much longer timescales and driven by environmental pressures?

The Missing Piece: Natural Selection

The genius of Darwin and Wallace was proposing natural selection as the primary mechanism. It wasn’t just that life changed, but how it changed. Individuals with traits that helped them survive and reproduce in their environment were more likely to pass those traits on. Over vast stretches of time, this leads to adaptation and the diversification of life.

So, while instruments are amazing for the details, the core idea of evolution was born from observation, geological evidence, and a shift in how we thought about time and the natural world. It took centuries for the intellectual and societal landscape to be ready for such a profound idea, and for thinkers to gather enough evidence to propose a robust theory.