It’s easy to think of automation as a modern invention, a product of silicon chips and complex algorithms. But the desire to have machines do our work, and do it tirelessly, is much older than you might imagine.

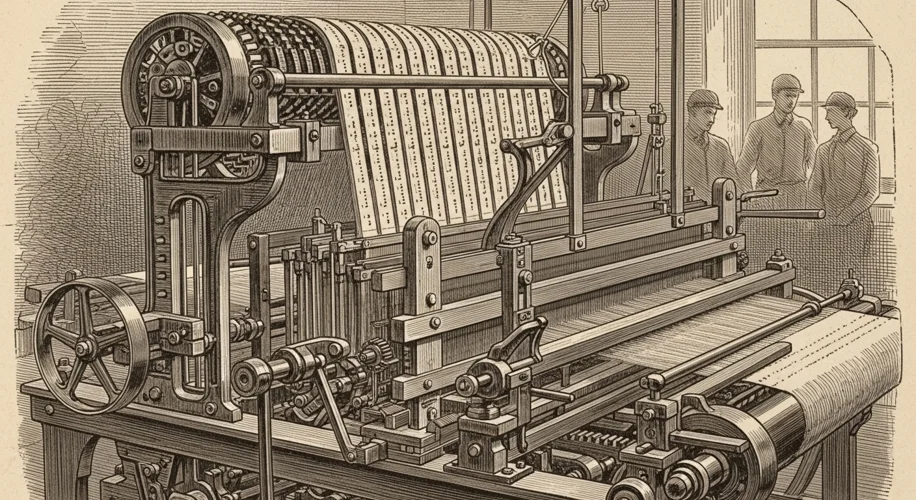

Back in the 19th century, a time of booming industrialization, people were already dreaming of automated factories. Think of the Jacquard loom, for instance. Invented in the early 1800s, it used punched cards to create intricate patterns in textiles. This was a marvel of its time, allowing for complex designs to be reproduced automatically, vastly increasing production speed and consistency. It was, in many ways, a precursor to programmable computers.

These early leaps forward were often hailed as triumphs of efficiency. Suddenly, factories could churn out goods at unprecedented rates. The focus was squarely on output, on maximizing what the machines could produce with minimal human intervention. The idea was simple: replace human labor with mechanical precision.

But this relentless pursuit of efficiency came with its own set of problems, a kind of cautionary tale we’re still grappling with today. When the Jacquard loom took over complex weaving tasks, it displaced skilled artisans. Their livelihoods, built on years of practice and expertise, were suddenly threatened by a machine. This wasn’t just about changing jobs; it was about fundamentally altering the relationship between people and their work.

Later, experiments with early automated factories in the late 19th and early 20th centuries faced similar tensions. While they promised greater output, they often created monotonous, repetitive tasks for the humans who still worked alongside the machines. The human element, the creativity and adaptability that skilled workers brought, was sidelined in favor of predictable mechanical action. There was also the ever-present concern about how these powerful systems could be controlled, or worse, misused. If machines could direct production so effectively, what else could they direct?

This history is particularly relevant when we look at today’s discussions about increasingly autonomous systems, especially in areas like warfare, as my previous post on drone swarms touched upon. The echoes of those 19th-century looms are loud. When we prioritize raw efficiency or speed above all else, we risk overlooking the human impact. We need to ask ourselves: are we building systems that serve us, or are we becoming subservient to the logic of the machine? The early pioneers of automation were driven by innovation, but perhaps they didn’t always fully consider the long-term consequences for the people whose lives their inventions would reshape. It’s a lesson worth remembering as we continue to automate our world.